Introduction

Roborovski dwarf hamsters (Phodopus roborovskii) are well known among hamster fanciers for being the most sensitive of the species in captivity. As the first captive breeding efforts were in the 90s, Robos have been present in the fancy for a very, very short amount of time.My first experiences with Robos were as a child, when I kept three females. They were incredibly skittish, nearly impossible to handle, and not particularly fond of interaction—but I loved everything about them. This early experience sparked my longstanding interest in animal husbandry, genetics, and selective breeding.

However, through selective breeding, the litters in my program has shown me how wonderful Robos can be. Milkbun Hamstery Robos are very docile, calm, and happily jump into the hand for a snuggle.

How do we improve temperament?

Many people are under the impression that the current temperament that is common in a species will be extremely difficult to change. However, that is not necessarily true. All of our domesticated animals, such as dogs and horses, were wild and difficult to handle generations ago. The principle of selective breeding and breeders who strive towards a temperament of their preference is how the demeanors of the animals will change. The earlier generations of my selection were much like the usual Robo, but through breeding and selecting the pups that showed the most docility and eagerness to interact with me, resulted in the bloodlines and individual hamsters that I have today.

I go much deeper into this principle in the latter section of my Breeding Program page.

Improving Temperaments in Robos: Nature or Nurture?

When I began with my foundation animals, I expected progress to be rather slow. They were “okay”, meaning they associated my presence with food, would take food from my hand, but wouldn’t approach me voluntarily and darted away if I attempted to pick them up.

However, I was very surprised that even in one generation, the improvement was quite exponential. One of my early females was a self husky (self is a term for ‘solid’, ‘husky’ is a color), I called her ‘Peach’. Peach was more nervous than the others – she would avoid touch at all costs, jump out of your hand, and hide at the sound of my voice. I was hesitant to include her in my program, as it could cause a setback, but her type (particularly the shape of her muzzle, eye set, ear shape and set) and natural condition were very nice. I paired her to the male with the best temperament I owned, a large blue pied male. He would climb on my hand voluntarily, but was very distrustful when I initiated touch.

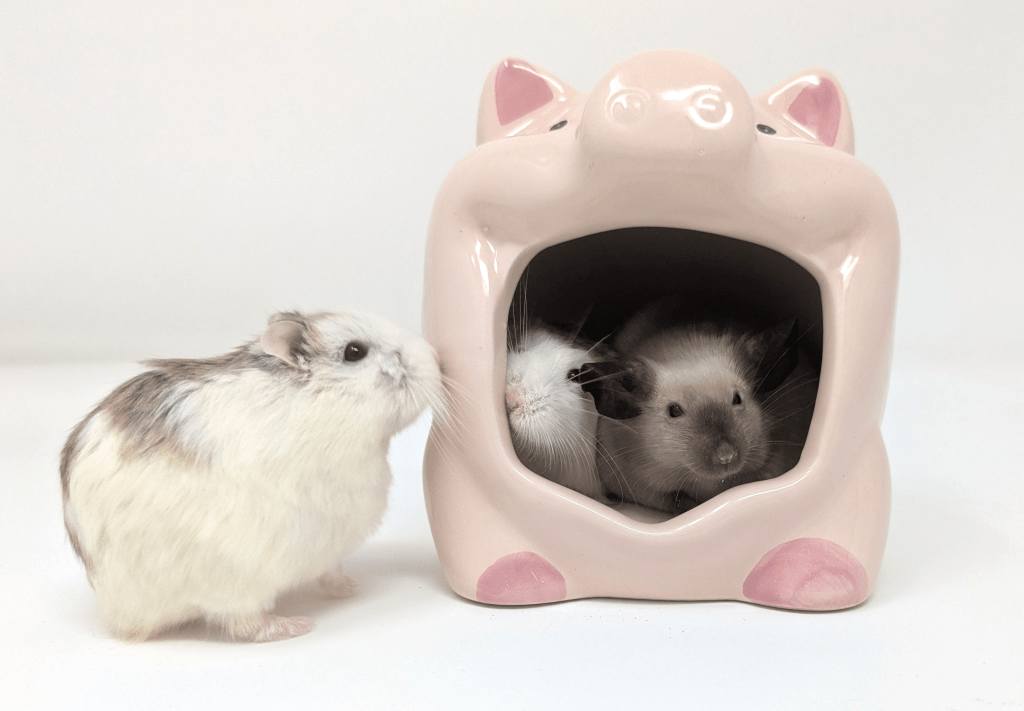

Above is a photo of the resulting litter, 3 self agouti females, 3 self white females, and 1 self white male. 7 pups is quite a large litter for this species of hamster (average litter size I have bred is 3-5 pups).

A commonly debated topic in animals (and humans) is “nurture vs. nature”. “Nature” meaning the genetics of fauna, which would be inherited characteristics – “Nurture” meaning the environment and upbringing. In this document for the AKC Canine Health Foundation, Dr. Jacqui Neilson discusses research done with rats and dogs to explore the genetic influence on behavior.

The consensus is that both genetics and environment contribute to animal temperament. From the difference between rodent and dog breeding I planned a rating system of 0-5. 0 being untouchable, 5 basically being a puppy. I put Peach at 1, her mate at a 3. The trio of agouti females I marked similarly at about a 2. I could pick them up, to an extent, but they clearly preferred to avoid me, and would ultimately jump out. Out of the three white females, there was a 1, a 2, and a 3. The female who put as a 1, was exactly the same as their mother, easily panicked. The female who was a 2 was just like the agouti females – not as nervous as their mother, but didn’t enjoy or seek me out. The female who was a 3, would crawl into my hand and climb up my arm when given the opportunity, but spooked slightly when picked up directly. The white male I considered a 3. He was the calmest out of them all, crawled into my hand, yet similarly jolted when disturbed.

As a breeding theory nerd, I was utterly fascinated by the results of every litter I bred. I noted the results of an outcross, linebreeding, and repeated pairings. I may break down my specific findings with each type of pairing in a different page, but I will wrap it up for now. Here is a video of a recent litter from late 2024. All of the hamsters in the video are the offspring of an agouti pied male, Milkbun Jolly Gingersnap, and a white female, Milkbun Charmmy Kitty – except for the agouti pied female (the white one with the darkest patches), she is their aunt.

The hamsters are in a spare container that I use for a variety of purposes. To inspect condition and temperament, take videos, place in temporarily while cages are being cleaned, feed live mealworms (I prefer not to feed insects in the enclosures, as the bugs are impossible to find in the bedding if they escape), and as a neutral area for breeding pair/colony introductions. (Note: Here is a link to an article I had written detailing Roborovski social behavior and cohousing)

On average, if I would place a pet store or rescue Roborovski in the container, the behavior I expect is very rapid pacing, jumping at a corner desperately, and when a hand approaches, pressing itself against the wall – ready to dart away. The topic of taming is also for another day, but the point is, the personalities of my Robos at my current generation are ones that I have found to be very sweet and awesome pets. I can pick any of them up one-handed without any issue, hold them gently on their backs, and they will just relax in my hand.

One might argue that my hamsters are friendlier because they were raised in my home and handled from 14 days of age. However, considering the range of temperaments I’ve experienced with the same environment, same level of handling with each and every pup, I would disagree with it to a certain extent. Of course, not being traumatized from a young age is very important, but genetics appear to take the largest capacity in determining their mannerisms. All of my litters receive a proportionate amount of handling, yet as they mature, it is abundantly clear how they will be.

Behavior of Roborovski in social settings

It is a common misconception appropriated in many hamster husbandry spaces that hamsters have a preference for solitarity and do not do well in social settings. But what is not taken into sufficient account, is that each hamster species is significantly different biologically, to the point that they are all classified as hamsters (and the classification Phodopus being shared by the Robo, Winter White, and Campbell) is actually quite misleading.

In the wild, Robos live in family groups, typically consisting of a breeding pair and their subsequent litters of offspring. This natural grouping is evident in captivity, as Robos tend to thrive in both terms of enrichment and comfort if they have their own to interact with.

We go more significantly into detail on this on the article I linked above.

Robos absolutely can live together, in fact, they typically prefer company. It’s often said that they must be littermates to stay together, but that’s not a requirement from my experience. I have longstanding colonies of female Robos that are unrelated — and it is not difficult at all to introduce new members of the colony.

Similarly to fancy mice, female Robos are typically pretty easy to keep together, and accept new members of the colony quite readily. Males, however, I’ve found can be trickier. Those who are familiar with rodent husbandry may understand that both breeders and owners heavily advise against keeping male mice (bucks) with individuals of the same sex. As they mature, mouse bucks will become heavily competitive and aggressive towards one another.

However, that information does come with a footnote. The mouse fancy (breeding community) in the UK has had a long history, with generations of dedicated breeders who have selected their mice to be as close to their ideal as possible. For some lines/breeders, one of the traits they have sought is producing bucks that will live harmoniously with one another. According to some, bloodlines that have yielded extremely laid back males can have difficulties with fertility — and it is suggested that perhaps it is due to a decrease in testosterone (which may cause male on male aggression).

How does this relate to male Robos? In general, I would say that Robos seem much closer in behavior to mice than the other hamster species. It is perfectly achievable to have larger groups of female Robos, like female mice are typically kept (though with certain considerations in environment, like making sure the enclosure is not too large. Is that surprising? We’ll get to that later….).

However, I do feel that the same-sex social status of male Robos is much more ambiguous. In the beginning, when scoping out whether my retired adult males who have sired offspring could co-exist, the answer very much seemed to point to “no”. When Robos are feeling hostile towards one another, it is quite apparent.